Highways and the West End

Like many other American cities in the 1960’s through the 1980’s, Charlotte used the construction of highway infrastructure to reinforce and strengthen the racial divisions and economic stagnation that had been created by enforced segregation of housing and education. The redlining maps commissioned by the Federal Housing Authority in the 1930’s were critical to decisions of where and what type of lending and housing neighborhoods received, and “redlined” areas were often doomed to a future of decay and neglect. These communities were often disproportionally poor and African American, and developers often shunned them for white areas after redlining made it impossible to secure federally backed mortgages for residents.

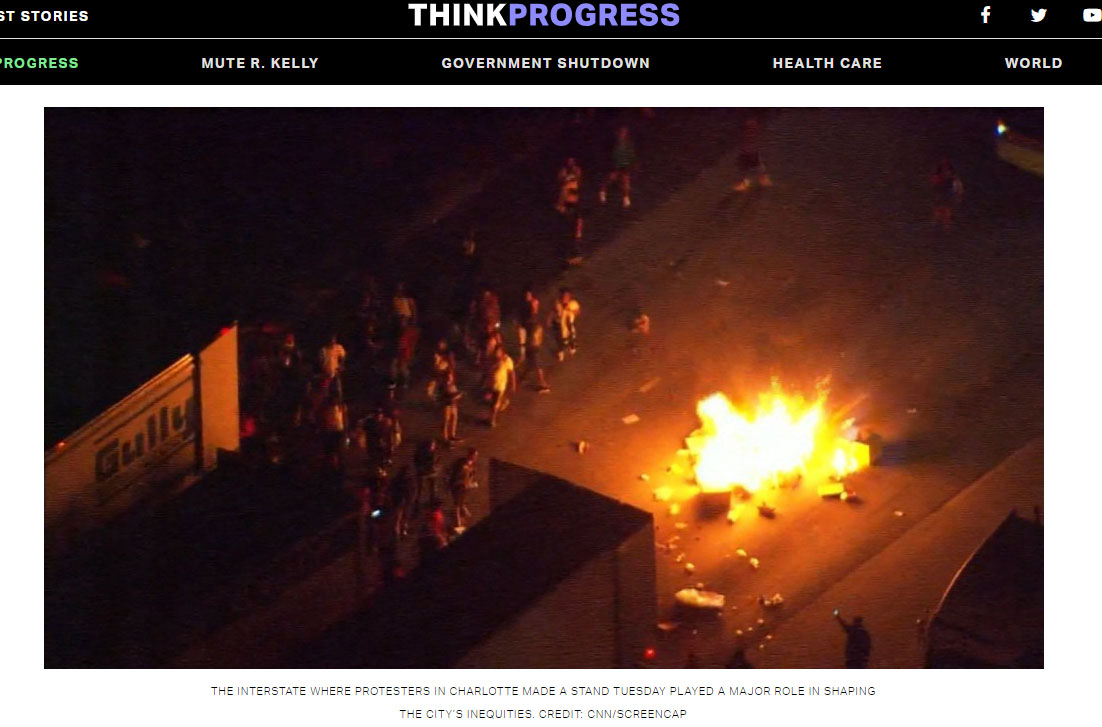

The expressway system was designed to speed Americans along in a changing world, but it was also designed to outline the future ghettos of the country. From coast to coast in towns like Oakland, Detroit, Denver, and Atlanta, vibrant African American pockets of culture and community were carved up and paved over with rings of concrete and skyscrapers under the pretext of “slum clearance” and “urban renewal” and families were displaced into areas where crime and drugs would breed.

In Charlotte, the vibrant African-American community called Brooklyn was demolished through urban renewal and its families and institutions were dispersed, often to the Historic West End where they were assimilated into the only other place in the city where black culture was thriving. In the 1970’s and 1980’s, much of the land on the West End became a target of Charlotte’s growing expressway system that would ultimately divide the richer white neigborhoods on the south end of the city from the poorer areas on the west and north sides. The city’s 20-year Thoroughfare Plan involved the construction of the I-77 loop, the Northwest Expressway (renamed the Brookshire Freeway in the 1970’s) and the North-South Expressway (now the John Belk Freeway) and the retrofitting of Independence Boulevard to form an inner loop around the core of the city.

Now referred to as I-277 and aptly called the “concrete spaghetti bowl” by the Charlotte Observer at the time, the two segments that impacted the West End were the I-77 loop that formed the western piece, and the Northwest Expressway which formed the northern edge. The Northwest Expressway was planned to cut through the McCrorey Heights neighborhood near JCSU, destroying part of the haven of fashionable ranch homes owned by the black middle class that was unique in Charlotte at the time.

The expressway displaced more than 240 families in the West End, and would also claim the Biddleville School and much of Irwin Avenue Junior High and the Lincoln Heights School. It also took most of the Biddleville Park, and several businesses and cultural institutions like the Sportsman’s Grill and the Club Bali. The corresponding I-77 loop destroyed many parts of Dalebrook and Oaklawn Park, two other vibrant black neighborhoods on the Westside.

Barack Obama’s Secretary of Transportation Anthony Foxx made it a personal crusade during his administration to highlight how federal infrastructure projects contribute to inequality and poverty and to direct funding to address these disparities. Foxx had plenty of personal experience with how that system worked, as he was raised in the Dalebrook community. “I grew up living with those barriers,” he said, “even though I had no idea how they came to be or what they really meant.”