West End Bombings

By 1965, the city of Charlotte had carefully cultivated an image as a progressive city that had not been marred by the violence that had fractured the South in the previously turbulent decade. Mayor Stan Brookshire and the white power structure had worked with moderate black leaders like Fred Alexander to take slow and measured steps towards peaceful change. In the eight years since Dorothy Counts was spit on and ultimately driven out as she tried to integrate Harding High School, Charlotte had stayed out of the national headlines of race relations. There was anger and resentment bubbling under the surface of this façade of peaceful coexistence, however, that would literally explode in November of that year.

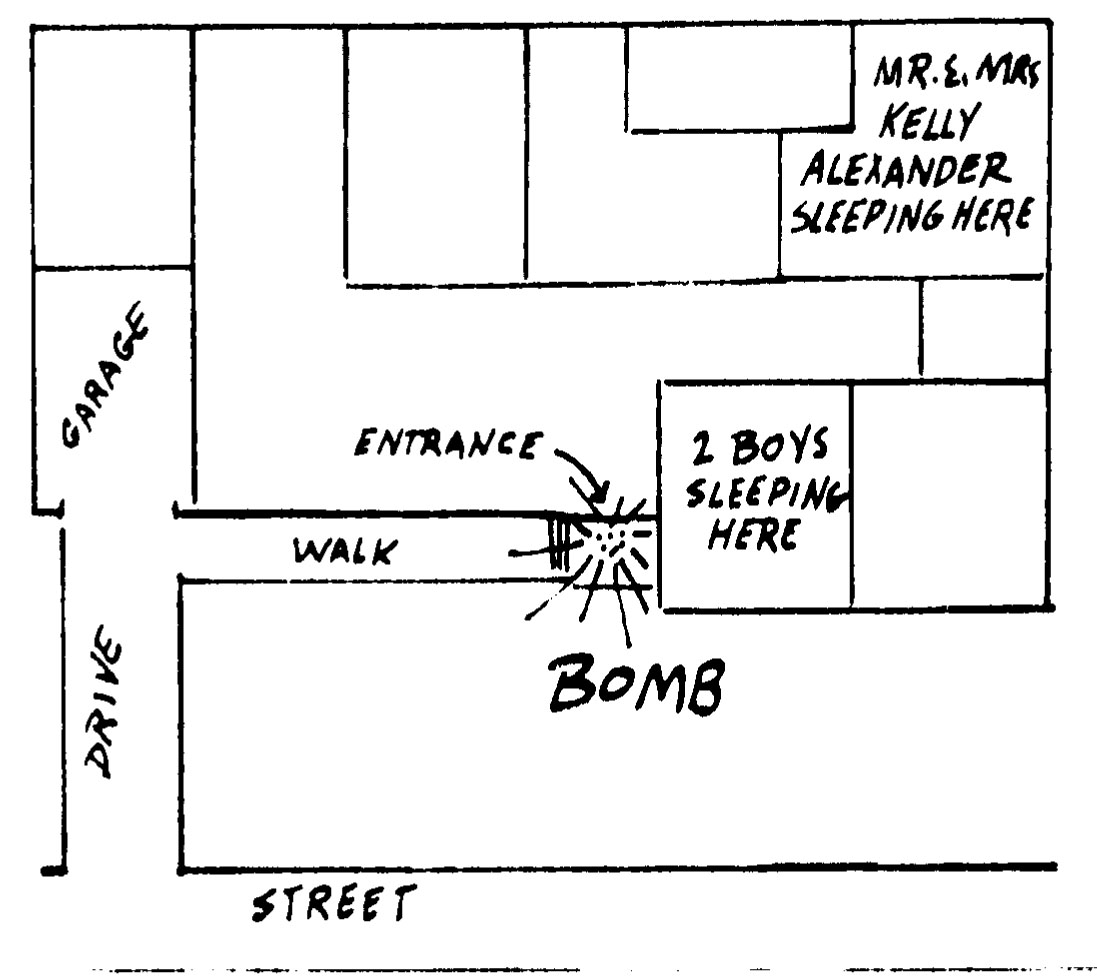

In the early morning hours of November 22, 1965, on the second anniversary of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas, a coordinated bombing attack was carried out on the homes of four civil rights leaders in the Historic West End area. The houses bombed were those of Reginald Hawkins at 1703 Madison Ave in McCrorey Heights, City Councilman Fred Alexander at 2140 Senior Drive and his brother Kelly, President of the state NAACP, at 2128 Senior Drive in University Park, and civil rights lawyer Julius Chambers at 3208 Dawnshire Drive in the Northwood Estates neighborhood. No injuries were reported even the families, including the children of Kelly Alexander and his wife, were home asleep at the time.

The headlines about the bombings spread around the country and Charlotteans expressed shock and outrage, but the reality of violence was not necessarily news to the black communities where they occurred and certainly not to some of those directly targeted; in fact they had been trying to get local police to take the threats more seriously. Despite a statewide manhunt no one was ever arrested for the attacks and the case, code-named CHARBOM by the FBI, has never been closed. Suspicion quickly turned to the Ku Klux Klan, but there were very few clues, no witnesses, and no real suspects. The bombings were not the last incidents of violence against the black community and their sympathizers in Charlotte either; on the morning of Feb 5, 1971, while the Charlotte desegregation case was before the Supreme Court, Julius Chambers’ law offices on West 10th street were destroyed by a fire set deliberately.

The night of November 22, 1965 was later referred to in the press as the “Pearl Harbor of the civil rights movement in Charlotte,” as some expressed that the result was the solidity of local black leadership and the further unification of black and white moderate leaders to affect change and avoid further incidents. It also laid painfully bare the undercurrent of racial tension in Charlotte and exposed the fact that the city was not immune to the violent tendencies of those who sought to resist efforts to desegregate schools and other public places. That tension still exists, and exploded recently during the protests and actions that followed the 2016 killing of Keith Lamont Scott, a black man, by Charlotte police officers. It will require continued dialogue between community members, police, government officials, and city leaders to heal the rifts that have always existed under the surface in Charlotte.